I practice in a very blessed land. One where I am right down the road from a night and weekend emergency clinic and there are no less than 4 specialty and referral centers within a 15 mile radius. I am never on call and I can always offer my clients the best possible care for their pets through referral. I love the opportunities this affords me and my clients. I get to continually learn from specialists and have peace of mind that my patients are being monitored when I’m not around.

Most days, I feel pretty lucky to live in a community that can support this level of veterinary medicine. Some days, I am reminded that there is a downside to this increasing standard of care.

Last week I arrived at the office to find that there was a walk-in emergency already waiting for me in a room. A sweet, 5 year old pit bull named Lilly lay pitifully on the floor. “I think she’s bloated,” Mom said. I wasn’t immediately convinced. Her stomach was a little distended, and she was depressed, but the bloats I’d seen before were typically in much worse shape—shocky and with massively swollen abdomens. Still, the x-ray confirmed Mom’s suspicions. I let her know the bad news—Lilly needed surgery. A board certified surgeon was already scheduled to come that day for a cruciate repair and could perform the procedure.

Mom wanted to proceed with treatment, but finances were extremely tight. I gave her some information on financing options and she went home to try to procure the funds while I began the initial stabilization. Shortly after successfully passing a stomach tube, I got a call to let me know that the family had been unable to come up with the necessary money for surgery.

I reached out to an online community of veterinarians I belong to, looking for advice on some way to save Lilly. “Why do you need a surgeon?” Someone asked. “A pexy is a pretty straight-forward procedure.” Maybe so, but I had never done one. What if it was more than just a gastropexy? What if the stomach had necrosed and I had to do a partial gastrectomy? Give me a complicated medical case any day, but an unpredictable and unfamiliar surgery? Lilly was the one whose stomach was literally tied up in knots, but I felt like mine was too.

The blessing of working so close to so many specialists was suddenly a curse. For many vets, GDV surgery is pretty routine, but not for me. Because there were so many people better than I to do the procedure, I lacked the experience and confidence to do it myself. Still, what was the alternative? I could have said “I’m so sorry for the position you’re in, but Lilly’s condition is serious. If surgery is not an option, we should let her go.” I couldn’t do that though. Instead, I told Mom that although I had never performed the surgery before, I would be willing to attempt it at a reduced cost.

I gowned up, scrubbed in, and made the cut. My fears were confirmed. A large portion of Lilly’s stomach was necrotic. I felt like I was in way over my head, but it was too late to turn back now. I was sure I was screwing things up. Some of the stomach contents had definitely contaminated the abdomen, I wasn’t convinced I had removed all of the devitalized stomach, and even after three layers of stitches in the gastric wall, I still wasn’t sure there wasn’t a leak.

Two days later, bright and active, and eating her small, prescription meals like gangbusters, Lilly went home. A couple days later she was back for a scheduled recheck and looking as great as ever. “Thank you Mom said. Saturday was my birthday and this was the best birthday present I could have asked for.”

Having access to the best care for my patients is wonderful, but I worry that veterinary medicine is moving to a place where only the best will do. If we can’t do it perfectly, we won’t do it at all. We’re practicing scared. We’re scared of not being perfect, we’re scared of being sued, of having our license challenged. These are legitimate fears, and sometimes we need to listen to them, but we can’t let them stop us from doing what we signed up to do—helping animals.

As veterinary medicine becomes more and more specialized, we are offering superior care to some, but are we also refusing care to others who can’t afford it? Are we stunting our professional growth? Are we denying ourselves the satisfaction that comes with pushing ourselves and making a difference? I put myself out on a limb for Lilly, and for days my thoughts were consumed by fears that I wasn’t good enough to help her. I was scared and stressed, but in the end, Lilly’s case was one of the most rewarding ones I’ve dealt with in recent memory.

I plan to continue to offer the best care to all my clients through referrals when warranted, but when that’s not an option, I won’t let fear keep me from taking a chance on those that truly need it.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the DrAndyRoark.com editorial team.

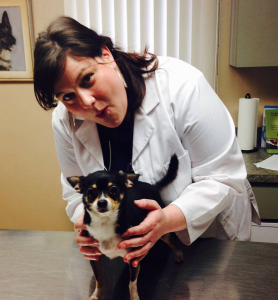

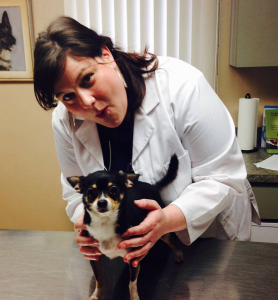

About the Author

About the Author

Dr. Lauren Smith graduated in 2008 from Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine and completed her clinical year at Cornell University. Her professional interests include internal medicine, preventative medicine and client education. Dr. Smith lives and practices on Long Island with her cat, Charlie and dog, Frankie and loves to read write and run in her free time. You can check out more of her writing at laurensmithdvm.com