Many patients never get the surgery they need because veterinarians or owners assume that a mass is cancerous. Worse: countless pets are euthanized based on the same assumption.

[tweetthis]Many pets never get the surgery they need because we assume a mass is cancerous.[/tweetthis]

It’s not uncommon for a referring veterinarian to call me in (I’m a traveling surgeon) to perform surgery on a patient with a “tumor in the spleen” or “spleen cancer.” I tend to call it a “mass in the spleen” until proven otherwise by a pathologist. Understandably, some clients often don’t want to put their (often older) pet through surgery if it’s likely to be cancer. But that’s obviously a decision based on their family vet’s assumption.

It’s not uncommon for a referring veterinarian to call me in (I’m a traveling surgeon) to perform surgery on a patient with a “tumor in the spleen” or “spleen cancer.” I tend to call it a “mass in the spleen” until proven otherwise by a pathologist. Understandably, some clients often don’t want to put their (often older) pet through surgery if it’s likely to be cancer. But that’s obviously a decision based on their family vet’s assumption.

The truth is, it sometimes doesn’t even matter if a mass is benign or cancerous. A benign mass can cause some very annoying signs depending on where it is located:

– A large, benign mass in the rectum can prevent a dog from defecating.

– A large, benign mass pushing on the trachea can cause severe difficulty breathing.

– A large, benign mass in the armpit can prevent a dog from using the leg normally.

These masses may have been benign, but they still caused some significant signs that dramatically affected the pet’s quality of life.

We recently did surgery on three patients. “Everybody” involved was convinced that they had cancer. But their owners just loved their pet too much and couldn’t put them to sleep without at least the benefit of surgery – and a biopsy.

Max* is a 13-year-old male Sheltie. X-rays revealed a large mass in the spleen. Based on the way it looked on ultrasound, the mass was believed to be malignant. Taking an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the spleen is possible, but it can be risky: the mass can rupture and bleed out. In addition, the biopsy can cause spreading or “seeding” of cancer cells.

Despite the odds, Max’s owner was interested in surgery. The mass was the size of a cantaloupe (in a Sheltie!), and looked really “ugly” (this is secret vet code for “Wow, this oughta be cancer”). Max recovered uneventfully. One week later, the biopsy came back as… benign! The mass was a myelolipoma, essentially a benign fatty tumor. Max is now expected to have a normal quality of life and a normal life expectancy.

Jake* is a 12-year-old male Cocker who had difficulty urinating. Ultrasound showed a large mass in his bladder. Bladder masses are much more often cancerous than benign. His owner elected to have the mass removed anyway. We took Jake to surgery and removed about one-third of his bladder! One week later, the biopsy came back as… benign! The mass was a leiomyoma, a benign tumor of the muscle. Jake should have a normal life expectancy and a normal quality of life.

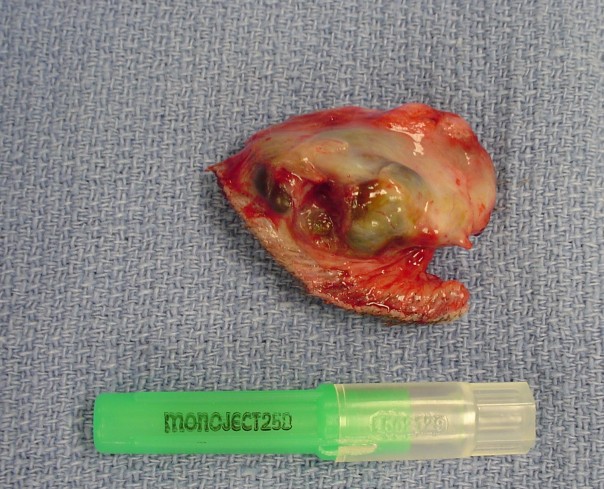

Praline*, a 9-year-old Labrador had a pretty big mass under the tail. She was referred for tail amputation, since the mass was thought to be cancer. For some reason – call it a gut feeling – I wasn’t too thrilled to do that, and of course neither was the owner. So we agreed to remove the mass only. After cutting into the mass after surgery, it appeared dark, so I was concerned it could be a malignant melanoma. One week later, results came back: the mass was benign! It was a cyst in a sweat gland. Again, this mass will not affect the patient’s life span, and Praline got to keep her tail!

So what is the moral of the story? Be humble and “never assume”…

[tweetthis]Does this pet have cancer? “Be humble and never assume”[/tweetthis]

I am perfectly aware that the diagnosis could just as easily have been “bad.” In fact, it was supposed to be, based on experience and statistics. But here are three older dogs, in the later part of their lives. They all were statistically “supposed” to have cancer. But these loving owners, willing to provide the best possible care for their pet, were not going to give up without a fight.

In fact, out of countless patients who did have cancer, I don’t remember a single pet owner ever regretting choosing surgery over euthanasia, no matter how little extra time we bought. The goals of tumor removal are to obtain a diagnosis, improve the patient’s quality of life (e. g. being able to urinate or defecate or breathe), increase life span, and decrease future risks (e.g. by preventing internal bleeding after a spleen mass bursts).

Think these are miraculous exceptions?

Far from that. It happens all the time. Within the past few weeks, we had Prince*, the 15-year-old cat with a huge liver “cancerous” mass which turned out to be a multitude of benign cysts. And Leo*, the 12-year-old Italian Greyhound with a huge “cancerous” tumor on the thigh, which report showed a perfectly benign fatty tumor (lipoma). And Frank*, a 12-year-old Doxie with a “cancerous” tumor on the ankle, that came back a ruptured benign cyst. The list could go on…

Over the years, I have become much more cautious when a pet owner asks me what I think a tumor is – benign or malignant. I simply answer that “I don’t have microscopic vision,” and that I just don’t know. Some clients hate this answer, but I would rather remain humble, than give a client unnecessarily poor odds or false hopes.

In the case of Max, Jake and Praline, three extremely dedicated owners were rewarded with an excellent outcome and hopefully many more happy years with their dogs.

[tweetthis]What happens when veterinarians call it “cancer” and are wrong?[/tweetthis]

Clinical photo credit Phil Zeltzman: BENIGN sweat gland cyst in the tail of a 9-year-old Labrador

* The stories are real, but patient names have been changed to protect their privacy.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the DrAndyRoark.com editorial team.